Wetlands as Borderlands: Where Land and Water Meet

Moving water connects these places, weaving the threads of the landscape together. The places where water and land combine—the riparian zones—mediate these connections, and what happens in these zones affects areas far beyond their boundaries.

— Nancy Langston, Where Land and Water Meet

Although it only describes riparian wetlands, this passage from Nancy Langston applies to pretty much any soggy ecosystem. For me, it has long suggested that wetlands might be usefully thought of as borderlands, albeit not in the conventional terms of state or political boundaries. Rather, wetlands are borderlands in that they are fundamentally “in-between” places—whether in terms of ecology, geography, or even culture and society—that have wide-ranging impacts.

Where land and water meet: physical borderlands

Wetlands exist simultaneously as both boundary and intersection. Which is to say, they mark the edges of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems while also embodying thorough hybrids of land and water. As such “liminal” (or borderline) places, they gain a truly unique identity of their own.

For both geographic and temporal reasons, the in-betweenness of wetlands also makes them a kind of borderland that can be particularly difficult to consistently define.

Geographically, wetlands rarely have distinct edges and exist instead as part of a continuous gradient between dry land and open water. How far into an estuary must I venture before I’ve left the wetlands at its edges? And if I find floating mats of grass and other plants scattered throughout that open water, what then? Meanwhile, depending on changes in topography, hydrology, climate, and resident animal and plant communities, the wettest parts of a wetland can even shift across a given landscape (the Tijuana Estuary’s river mouth, for example).

Temporally, wetlands might be continuously, seasonally, or only infrequently wet. How often and how persistently must a place flood (or drain) to be defined a wetland (or not)? Similarly, wetlands can come and go quite easily over time, emerging or receding into the terrestrial and aquatic worlds at their edges through sinking soils, ecological succession, climate change, or even through biotic activity (the building or collapse of beaver dams, for example).

What makes them so dynamic? Well, all that slow-moving water makes for a host of very distinctive ecosystem functions. For a start, wetlands serve as critical habitat for a variety of mammals, fish and shellfish, amphibians, and birds, many of which might be endangered or threatened. It also probably goes without saying that wetlands harbor very distinctive plant communities, from spanish-moss-draped bald cypress and tupelo gums to carnivores like venus flytraps and pitcher plants.

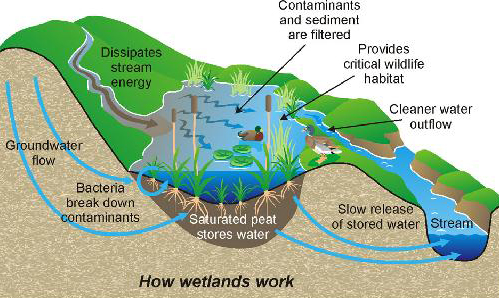

Additionally, in gathering and retaining slow-moving water, they help recharge aquifers and provide crucial buffers for flood and storm-surge mitigation. At much larger regional and global scales, wetlands perform valuable ecosystem services by acting as sites for carbon sequestration, de-ntirification of agricultural runoff, and balancing global sulfur cycles. In a related fashion, wetlands, often described as the “kidneys” of watersheds, play important filtering roles for the waters that, no matter how sluggishly, move through them. Wetland biology, topography, geochemistry, and hydrology all uniquely combine to render these landscapes crucial sinks for excess nutrients and toxic chemicals.

And again, that sluggish water is really important. It’s not only the critical condition for sustaining these water/land hybrids, it also transforms wetlands into a very particular kind of node in a watershed’s network of streams. I’ve often thought of watersheds as collapsing distance. Which is to say, whatever happens upstream often leaves its signature somewhere downstream. Wetlands—as places in the watershed where land and water are in close, prolonged contact—are where that upstream signature often gets rendered a little more visible. Whether in the form of eroded upland sediments, fertilizers from agricultural runoff, industrial toxics, or even pharmaceuticals in urban wastewater, upstream detritus accumulates in wetlands thanks to the combined forces of slack water, ecology, and topography. As places so thoroughly in between land and water, I imagine wetlands to be almost like the connective tissues of watersheds.

Landscapes on the periphery?

Riparian meadows and backswamps, estuaries and deltas, coastal marshes and inland bogs, and so on aren’t just dynamic ecological and geographical borderlands, however, they’re also fundamentally cultural and social ones as well. I’ve mentioned before that Ann Vileisis’s watershed (see what I did there?) book, Discovering the Unknown Landscape, highlights the ways the Europeans and their descendants that occupied North America have long scorned watery landscapes. Her work is revelatory for its insights around the intersecting ways culture, politics, and ecology have played out in the history of American wetlands, frequently with depressingly destructive results. Indeed, Vileisis points to what seems to be a trend wherever western modernity has taken root: the draining and dredging of watery landscapes. Wetlands around the world are increasingly threatened, if not disappearing entirely.

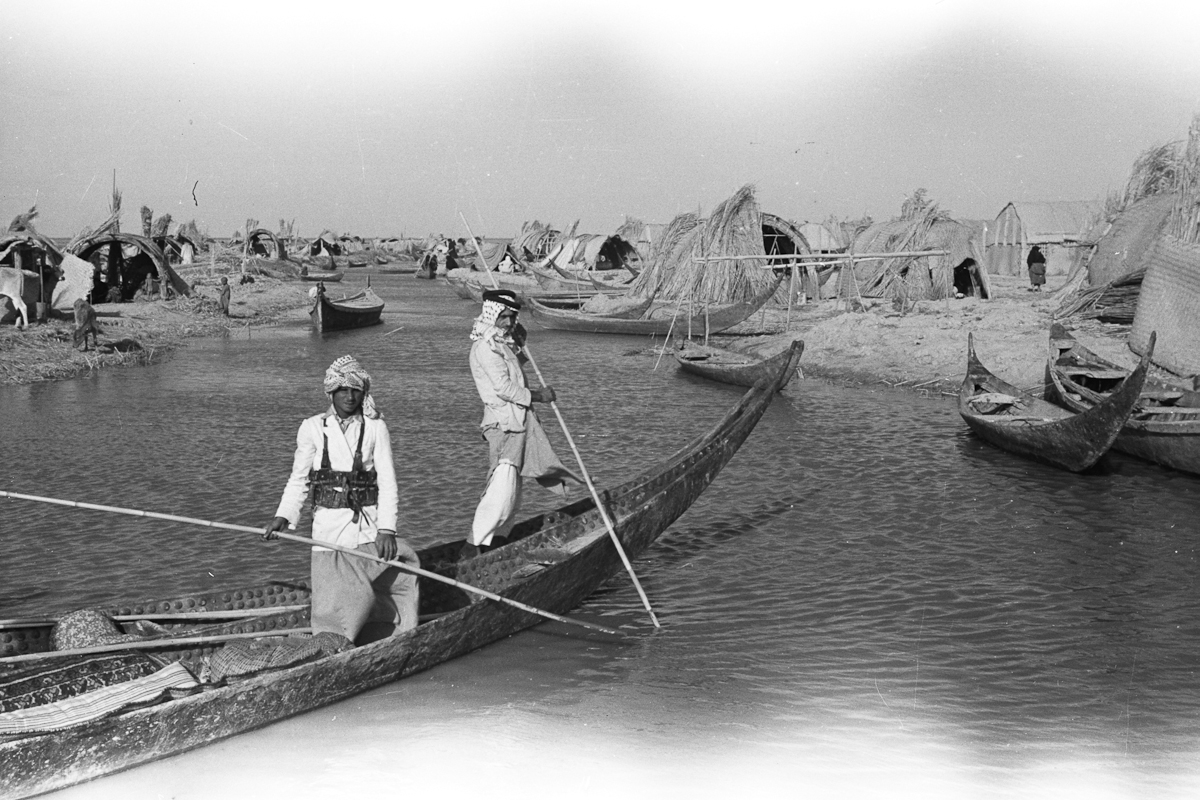

Yet, as I’ve also mentioned before, Vilesis’s narrative, aside from discussing Native American use and occupation of wetlands, also obscures some of the fundamentally human histories of these places. At the very least, though wetlands may have been anathema to Euro-Americans, that still leaves the long, if not always intensive, histories of human occupation in other watery landscapes around the world.

Landscapes of encounter

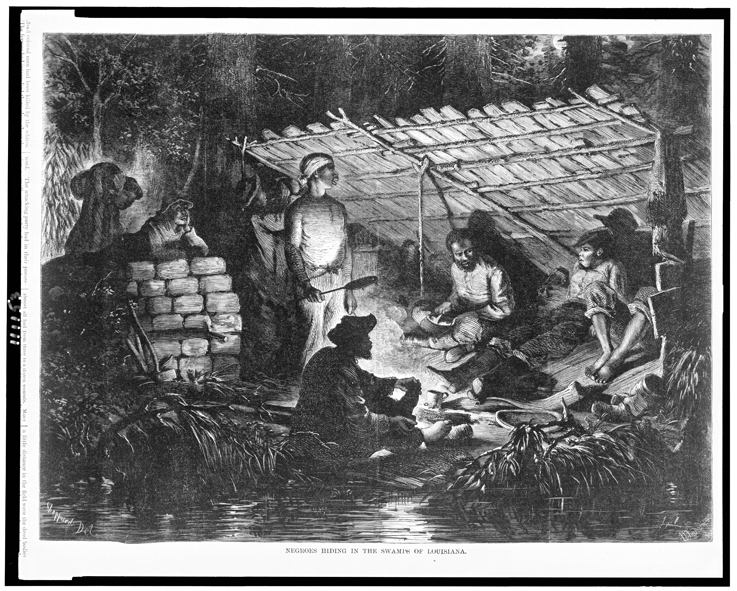

But, even if we were to focus only on North America (as my research does), I don’t think a narrative of derision, resource extraction, and destruction—followed by snippets of redemption in the environmentalist late-twentieth century—tells the entire story. For one, even if the majority of Euro-Americans shunned wetlands, watery landscapes often acted as refuges for marginalized peoples in the New World, from displaced Native Americans and Cajuns to escaped slaves and other fugitives. Though these histories might on the surface justify the claim that North American wetlands were “landscapes on the periphery,” that phrase doesn’t do much to reveal the ways such landscapes also served as sites of encounter between the margins and the core.

Imagining wetlands as borderlands instead of peripheries—that is, as places that imply encounter and exchange, rather than marginality and obscurity—allows much more room for moving them to the center of historical and geographical questions about nature and society. Rather than simply being wild places on the edges, edges that have receded with ever greater human transformations of the environment, wetlands as borderlands become busy places full of deeply human questions.

For example, what was life in Louisiana swamp or marsh communities actually like and how did places like New Orleans, or the reclamation efforts of planters and other entrepreneurs, intrude on their lives? Or, how did wetlands facilitate the establishment of fugitive “maroon” societies of escaped slaves? How did these colonies participate in clandestine slave communication networks that tied “civilized” plantations to unruly marsh and backswamp? Similarly, how did they manage encounters with bounty hunters, loggers, and other emissaries of of the metropolitan core?

All of this is to say nothing of the succeeding waves of colonization—each accompanied by their own explorers, resource harvesters, and traders—that spread over southern Louisiana. From French to Spanish, back to French, and finally to the Americans, the watery landscapes of the Mississippi River’s lowest reaches were fundamentally sites of knowledge exchange, cultural encounter, and both conflict and accommodation.

Of course, the region was distinguished by political boundaries for some time, making Louisiana a much more conventional borderland. But the cultural and economic exchanges that distinguished the colonial period also persisted long after those political boundaries dissolved. Those succeeding waves of colonial occupation and their creole (or hybrid) cultural legacies took place largely because of the Mississippi River watershed’s role as a vital transportation network that spanned over two-thirds of the continent.

Given that crucial role of the river delta, it’s hard for me to imagine southern Louisiana’s borderlands history (in the more conventional sense of the term) wasn’t just as profoundly shaped in some way by its wetlands as by its shifting national boundaries.

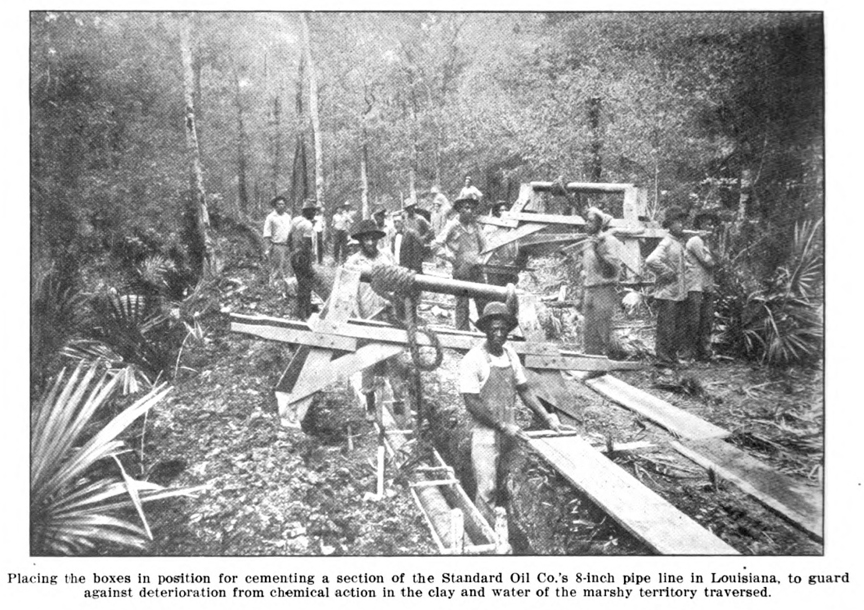

Wetland frontiers: natural resources, land reclamation, and human bodies

Besides being borderlands of encounter between the marginal and the powerful or between vastly different cultures and economies, wetlands in my research area were also important resource frontiers. Logging in Louisiana swamps at one time counted for a majority of cypress lumber extracted in North America, while logged-over swamps and treeless marshes also saw a variety of aggressive attempts at being “reclaimed” or otherwise developed for agriculture, oil and gas extraction, and even residential communities. Certainly, scholars like Ann Vileisis have told these stories of extraction and drainage in great detail. Yet the ways logging, oil and gas development, and wetland reclamation also represented an ever-shifting borderland between wild and improved land receives little attention.

How did these industries and their laborers adapt to working in these watery landscapes? What happened culturally, economically, environmentally when a new logging town sprung up in the midst of a Louisiana swamp only to be abandoned and recede back into “wilderness” (albeit a dramatically altered one)? What new technologies did logging or petroleum industries bring to wetlands that enabled them to do their extractive work and how did those new technologies transform wetland ecosystems into new, part-humanized, part-wild landscapes? These are just a handful of questions that arise when we consider wetland resource frontiers as landscapes of adaptation and hybridity rather than simply as sites for disappearing wilderness.

Finally, and I might be pushing the borderland metaphor here, all of these stories necessitated deeply visceral encounters between human bodies and an inhospitable environment. People are, by nature, not so well-adapted to watery places. To state the painfully obvious, we lack the right kind of eyes and skin, to say nothing of fins, webbed appendages, or gills to comfortably navigate and inhabit soggy places. Swamps and marshes present some of the most challenging environmental conditions for human beings. Though they might have rarely risked starvation, people living and working in wetlands faced water and vector-borne diseases, hostile wildlife, exposure, and even drowning on a daily basis. Compound those dangers with the facts of being a hunted fugitive or the risks of operating temperamental floating sawmills, logging equipment, or dredges and other machinery, and wetlands inevitably became dramatic sites of confrontation between a fragile human body and a decidedly “other” landscape.

Porous places: boundary crossings in watery places

In bringing this post to a close, a disclaimer/apology is in order: I’ve tended toward more abstract, imprecise concepts and hand-waving than I would like. Of course, that fulfills one of the original goals of this blog: a means of thinking (out loud) through dissertation ideas and questions as they evolve. And this particularly idea is definitely one in progress.

So, yes, wetlands are clearly redolent of many kinds of historical boundary crossings, though I’ve only suggested a handful here: aquatic/terrestrial, periphery/core, marginal/powerful, other/familiar, body/environment. But there are also onceptual risks in gathering these boundary-crossings under one wetland roof, from Jay Taylor’s concern over imprecision (see his “Boundary Terminology” article listed below for more on this), to producing unhelpful dualisms.

One of our capacities as creative, thinking creatures is analogy and, really, it’s possible to analogize pretty much any one thing to any other. If I start seeing borderlands everywhere, they cease to become useful explanatory metaphors. The same goes for other concepts that have been bubbling away as I undertake my research: permeability, porosity, membranes, etc..

That said, I’ve also already been rewarded a few times in the archives by keeping these concepts at the forefront of my thinking (more on those rewards in future posts). The trick will ultimately be to make sure that—whether I’m speaking of borderlands, porous places, or permeable membranes—each of my arguments actually gains analytical traction from those metaphors, rather than just conceptual window-dressing.

So, if you have thoughts on wetlands as borderlands, or on thinking about non-national, non-political borderlands in environmental history or geographical scholarship, drop me a comment. And thanks for reading.

Further Reading

Buchanan, Thomas. Black Life on the Mississippi: Slaves, Free Blacks, and the Western Steamboat World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Campanella, Richard. Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans. Lafayette, LA: University of Louisiana, 2008.

Colten, Craig. An Unnatural Metropolis: Wresting New Orleans from Nature. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

Davis, Donald. Washed Away?: The Invisible Peoples of Louisiana’s Wetlands. Lafayette, LA: University of Louisiana, 2010.

Hall, Gwendolyn Midlow. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Langston, Nancy. Where Land and Water Meet: A Western Landscape Transformed. University of Washington Press, 2003.

Lockley, Timothy James. Maroon Communities in South Carolina: A Documentary Record. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2009.

Mancil, Ervin. An Historical Geography of Industrial Cypress Lumbering in Louisiana. PhD Dissertation, Louisiana State University, 1972.

Mitsch, William and James Gosselink. Wetlands. New York: Wiley, 2000.

Sellers, Christopher. “Thoreau’s Body: Towards an Embodied Environmental History.” Environmental History 4, 4 (1999): 486-514

Taylor, Joseph. “Boundary Terminology.” Environmental History 13, 3 (2008): 454-481.

Theriot, Jason. Building America’s Energy Corridor: Oil & Gas Development and Louisiana’s Wetlands. PhD Dissertation, University of Houston, 2011.

Vileisis, Ann. Discovering the Unknown Landscape: A History of America’s Wetlands. Washington, DC: Island Press, 1997.

11 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

Adam,

I want to give this some more thought and respond properly, probably with a pingback post at Stillwater Historians. Physical borderlands. I’m drawn to it. It seems to have the capacity to draw together some of Dan Flores’ thinking about bioregions with Richard White’s skillful melding of cultural and ecological exchange zones in The Middle Ground, while also side-stepping some of the more obvious limitations of the conventional borderlands school. I, too, work in a region of numerous, complex borders. Dealing in resource policy poses the inevitable complication of trying to resolve the discrepancies between jurisdictional boundaries and ecological ones. But my region also contains the U.S.-Canadian border of the east coast. And while I’ve welcomed the opportunity to dabble in issues of transnational management and environmental diplomacy, I’ve been resistant to engage with the more conventional borderlands studies–feeling that they are too narrow and limiting. Physical borderlands. I like the thinking behind it, but what about something that embraces the layering, almost GIS-style layering through storytelling (visual and textual), that I think we’re both dancing around? Can we refine a term and a way of thinking that captures that–the way ArcMap can lay a political map over a geo map over a topo map, over a nautical chart?

Sorry, now I’m using your blog to think out loud too!

Rob:

Thanks, as always, for your thoughtful comments. And, please, no apologies for thinking out loud—-I welcome it! You’ve definitely picked right up on what I’m trying to feel out and I’m grateful for that. The layering idea absolutely appeals to me and isn’t one I’d thought of. All in all, it seems like we’ll have a lot to talk about as we each move forward on our projects. Maybe one of these days we can set up some kind of dedicated attempt—-whether a panel, round table, article, shared blog post, multimedia web project (although that may be ambitious, *grin*) or whatever–to hash some of this stuff out together.

Hey Adam–This post, like all the posts that I’ve had time to read on your blog, is filled with fascinating thoughts and images. Cheers from Sweden, which is rich in mires and other liminal spaces. Nancy

Nancy: thanks for your generous comment! I had no idea you were reading. Things have obviously slowed down *a lot*, largely thanks to my lecturing for the first time this semester, but Porous Places should be up and running again starting in December. I’m looking forward to hearing about what you’ve been up to in Sweden sometime.

[…] ← Previous […]

[…] Where Land and Water Meet. Porous Places: a Blog about Watery Landscapes. Available at: http://adammandelman.net/2012/06/01/borderlands/ [Accessed: 10 June […]

[…] The “edge” between land and water heavily influences the way we organize ourselves and our activities geographically. Access to potable water is vital to human survival on a biological level. However, we also derive immeasurable cultural, economic, environmental, and aesthetic value from our coastlines, streams, and wetlands. Historically, many of society’s most celebrated accomplishments required a robust understanding and management of the transitional boundary between land and water and, arguably, many of society’s greatest mistakes stemmed from a failure to adequately conceptualize and govern this boundary (Edge Effects’ own Adam Mandelman has captured many of these watery problems and possibilities at Porous Places). […]

[…] The “edge” between land and water heavily influences the way we organize ourselves and our activities geographically. Access to potable water is vital to human survival on a biological level. However, we also derive immeasurable cultural, economic, environmental, and aesthetic value from our coastlines, streams, and wetlands. Historically, many of society’s most celebrated accomplishments required a robust understanding and management of the transitional boundary between land and water and, arguably, many of society’s greatest mistakes stemmed from a failure to adequately conceptualize and govern this boundary (Edge Effects’ own Adam Mandelman has captured many of these watery problems and possibilities at Porous Places). […]

[…] The “edge” between land and water heavily influences the way we organize ourselves and our activities geographically. Access to potable water is vital to human survival on a biological level. However, we also derive immeasurable cultural, economic, environmental, and aesthetic value from our coastlines, streams, and wetlands. Historically, many of society’s most celebrated accomplishments required a robust understanding and management of the transitional boundary between land and water and, arguably, many of society’s greatest mistakes stemmed from a failure to adequately conceptualize and govern this boundary (Edge Effects’ own Adam Mandelman has captured many of these watery problems and possibilities at Porous Places). […]

[…] “Porous” places like Dagobah, where the difference between land and water is tenuous, have long provided refuge for social […]

Fascinating piece Adam. Wetlands are viewed as sort of the armpit of lands, with an importance of most of the other organs. Great research on some of the US history pertaining to wetlands and marshes. Glad I stumbled on it!