California’s Water Nightmare

It’s been a horrendous winter as far as unusually extreme weather goes. The UK has been drowning for weeks and the Upper Midwest has been utterly frozen. Life in Madison this season has felt almost as if the mile-thick ice sheets of 20,000 years ago had stopped by to check on their old stomping grounds. California, meanwhile, has experienced its driest year in over a century, dramatically compounding an already unbearable drought.

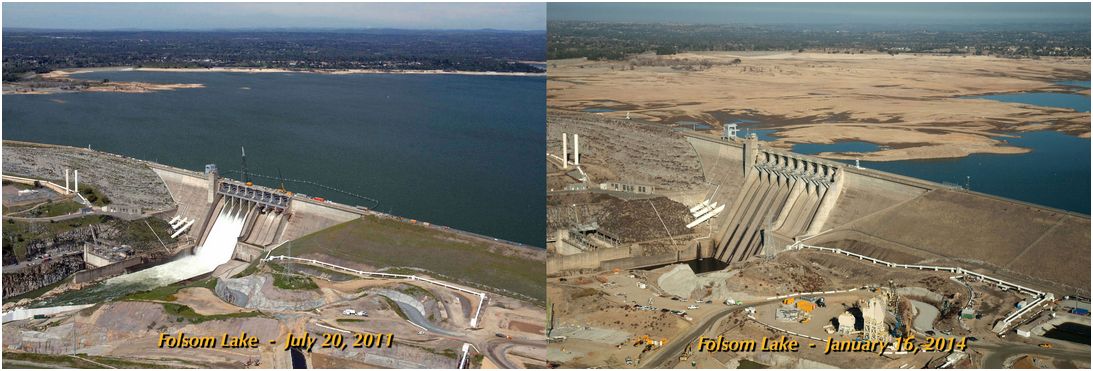

The Atlantic Cities blog just posted some great images of Folsom Lake illustrating the severity of the situation.

John Metcalfe writes:

Two-and-a-half years ago, this reservoir was at 97 percent of its capacity (and 130 percent of its historical average for summer). But last month it was as if somebody had pulled out a massive sink plug and drained the lake into a quagmire. The lake was at a mere 17 percent capacity, and 35 percent of its historical average, with vast stretches of its basin the concrete color of the nearby Folsom Dam.

Meanwhile, at the end of January, the State Water Project announced for the first time in its 54-year history that it would no longer supply water to any of the public agencies it serves, leaving about 25 million residents and 750,000 acres of farmland to fend for themselves.

And the shortage of rain and snow is affecting a lot more than agriculture. The New York Times reported in early February:

Near Sacramento, the low level of streams has brought out prospectors, sifting for flecks of gold in slow-running waters. To the west, the heavy water demand of growers of medical marijuana — six gallons per plant per day during a 150-day period — is drawing down streams where salmon and other endangered fish species spawn. . . . Without rain to scrub the air, pollution in the Los Angeles basin, which has declined over the past decade, has returned to dangerous levels. . . . In the San Joaquin Valley, federal limits for particulate matter were breached for most of December and January.

But agriculture is by far the biggest consumer of water in the state. As much as people might be grumbling about the ski season (or lack thereof) in the Sierras or as much as the drought is exacerbating pollution, we have to talk about agriculture. The figures differ, depending on whether you include only water diverted for human use, the total water circulating in the environment, or a number of other factors. Under California’s old monitoring system—which only counted water applied for economic uses—about 80% of the resource went to agriculture and the remaining 20% went to urban areas. Measures that take into account environmental needs, place the balance at somewhere around:

40-60% agriculture, 20-40% environment, and 10-20% urban.

And to achieve that balance, in a large, ecologically diverse, but primarily dry state, there’s a whole lot of engineering going on.

Alexis Madrigal’s latest feature for the Atlantic is about Governor Jerry Brown’s $25 billion Bay Delta Conservation Plan. After half a century of engineering (begun, in fact, by Jerry’s father, Governor Pat Brown), the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta is, in Madrigals’ words, “some of the most important plumbing in the world.”

Without this crucial nexus point, the current level of agricultural production in the southern San Joaquin Valley could not be sustained, and many cities, including the three largest on the West Coast—Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Jose—would have to come up with radical new water-supply solutions.

But, as Madrigal reveals, the current system is as destructive as it is productive. Alterations to the region’s hydrology have wrought havoc on native fish populations and brought the delta ecosystem to the brink of collapse. Never mind the fact that the “plumbing” system’s levees and other infrastructure are in real danger themselves, especially whenever the next earthquake strikes.

Brown’s current proposal is supposed to simultaneously fix the plumbing, restore thousands of acres of wetlands, and reduce the huge impacts the existing system has on native fish populations and other wildlife.

It’s an expensive, risky, deeply controversial project that carries all sorts of complicated social, political, economic, and—of course—ecological stakes. Madrigal’s piece is a must-read that not only outlines those stakes, but also delves into the lives and livelihoods of delta residents. Indeed, many delta families have ancestors who first carved farmland out of the swampy estuary in the mid-nineteenth century. The proposed changes will be hugely disruptive for people who’ve inhabited the delta for generations.

Of course, in a mostly arid, extensively cultivated state, it may be unsurprising that a sprawling watery landscape like the delta could go unscathed by California’s profound thirst. Madrigal puts it nicely: “According to the logic of half a century ago, water in a wet place does humans no good. Water in a dry place? Well, that’s Los Angeles.”

It’s not just the state of California that’s involved in this game of ecological arbitrage, however, but the entire country. We’re all implicated in California’s thirst.

As this great piece from Mother Jones reveals, water connects people and places in ways, that while sometimes surprising or easily overlooked, have profound consequences.