Memory and the Material World

Update: Virginia Hughes, whose original story about a new study in mice epigenetics inspired this post, has updated her coverage of that research. Find the link at the bottom of this page.

Over the last few decades, scholars from across the social sciences and humanities have been hard at work building an interdisciplinary field around the study of memory. Historians, anthropologists, psychologists, and many, many more have produced some fascinating conversations about the ways people remember and forget, and all the consequences cascading from those two phenomena. It’s a fascinating body of work and includes research devoted to everything from the study of technology and emotion to the multi-generational impacts of trauma.

As a geographer and environmental historian, I started really loving this work when scholars began turning the study of memory outward to incorporate landscapes and physical stuff in the world. Where memory was long instinctively understood to be ephemeral, interior, and psychological, memory studies was looking at the ways remembering and forgetting materialized beyond the realm of subjective consciousness.

Monuments and memorials, place names, architecture, ruins, and even the physical sensations of people’s bodies as they revisit places of trauma all made research on memory suddenly geographical, physical, and embodied.

Meanwhile, I’ve long believed that environmental history, with its enthusiasm for unconventional historical “documents” discoverable in present-day landscapes, is fundamentally concerned with memory. In being attentive to the ways past phenomena and events persist tangibly in the present, I like to think environmental historians reveal the ways that the physical world “remembers.” Two examples from my own work are these hub-and-spoke patterns in Manchac Swamp and this “blue hole” at Davis Pond.

But I should also say that I think of “memories” being embodied in the physical world in a much broader sense than these landscape-scale historical documents, or even the smaller-scale material culture of things like buildings, fenceposts, and saw-marks.

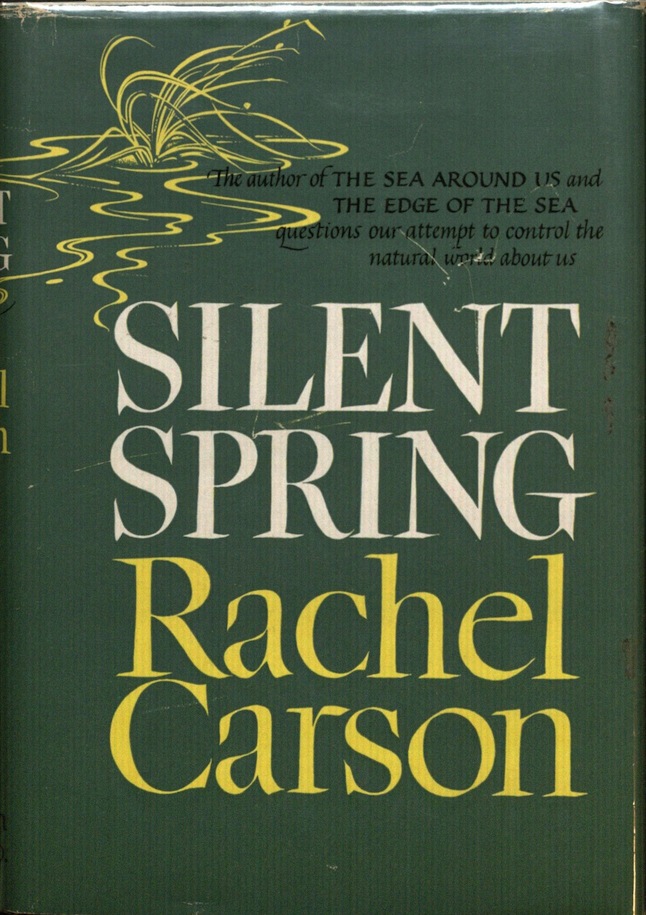

Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book Silent Spring revealed that environmentally persistent pesticides like DDT could not only accumulate in living tissues over time, but could also cause health effects long after the moment of exposure. Foreshadowing present-day concerns over dioxins, PCBs, and BPA, Silent Spring suggested that our bodies could become a historical archive of toxic exposure. Ultimately, the people and animals that die from the cancers and immune, endocrine, and nervous-system disorders wrought by these poisons become biodegradable memorials to chronic environmental toxicity.

But much like the ways trauma can be remembered and felt across generations, some toxic exposures get passed down through a victim’s children and grandchildren. Over the last decade, researchers in environmental toxicology have begun looking at the science of epigenetics to find evidence of toxic exposure that gets passed down through generations. This idea would normally fly in the face of our understanding of genetics, in which only changes to an organism’s DNA can be passed on to its descendants. The “epi” in epigenetics, though, refers to stuff happening outside the genetic code. These are not mutations. Rather, these are changes in the ways genes get expressed or suppressed (“switched on or off”) over the life of an organism. And remarkably, those changes in expression and suppression not directly encoded in the parent’s DNA can actually get passed down to their offspring.

This is a pretty controversial field of study, since it demands a re-evaluation of some of the core assumptions of genetics, but researchers have managed to demonstrate actual mechanisms (e.g., histone methylation) that produce epigenetic inheritance.

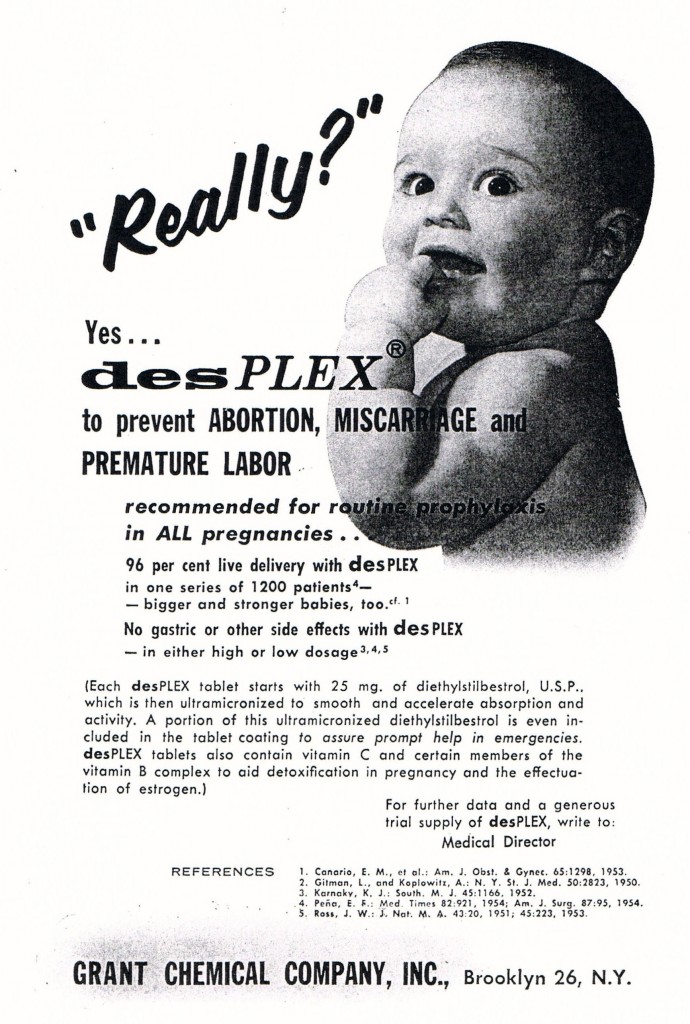

So, for example, mice exposed to the endocrine disruptor diethystilbestrol (DES) developed abnormalities in genes associated with uterine cancer. Offspring born two generations later still presented those abnormalities.

Between the 1940s and 1960s, women were prescribed DES to prevent miscarriage. Although it increased their risk of breast cancer to some degree, the most tragic aspects of DES exposure became apparent when their daughters, exposed in utero, saw dramatic increases in rare reproductive cancers much later in life. Because of the long lag associated with these health effects, epigenetic research is only just beginning on DES granddaughters. One study, however, has already suggested DES granddaughters are at higher risk for ovarian cancers.

DES daughters and granddaughters have to cope with chilling multi-generational memories of toxic exposure, memories that tragically manifest in their bodies. These memories, along with other endocrine disruptors showing transgenerational effects (like this fungicide), also demand significant rethinking not only of our understanding of environmental pollution, but also our individual health histories.

But epigenetics isn’t content to blow our minds just when it comes to poisons. A new, especially controversial paper found evidence that actual, literal memories might be passed on epigenetically as well. That is, researchers found that offspring could inherit psychological phenomena through biological material. Let me emphasize that distinction. Research has consistently shown that trauma gets passed down through generations. The children of Holocaust survivors, for example, have been famously affected by their parents’ suffering. The mechanism here, though, is social, not biological.

Neurobiologists Brian Dias and Kerry Ressler have suggested something entirely groundbreaking by revealing evidence of a biologically inherited fear response. Here’s Virginia Hughes writing for National Geographic’s Phenomena blog:

Now a fascinating new study reveals that it’s not just nurture. Traumatic experiences can actually work themselves into the germ line. When a male mouse becomes afraid of a specific smell, this fear is somehow transmitted into his sperm, the study found. His pups will also be afraid of the odor, and will pass that fear down to their pups.

The paper is yet to be published and has only been presented at scholarly conferences so far (here’s the abstract). And it’s understandably caused quite a stir. After her initial blog post, Hughes actually posted a fascinating round-up of the ensuing scientific debate on Twitter. But, if borne out by peer review and further study, the research will radically advance the field of epigenetics.

As far as this blog is concerned, it would also have a huge impact on how we understand memory and its relationship to the world at large. After all, it would suggest that environment influences organisms in ways that we’ve rejected for quite a while. The notion that the psychological and emotional dimensions of environmental experience could be biologically passed down through generations is pretty wild. Right now it smacks of pseudoscience, or at least science fiction. But just imagine: what if our bodies were permeable to those kinds of interactions with the environment? What if our emotional encounters with nature and landscape were somehow, deep in our cell nuclei, remembered by our children, and their children’s children, and so on?

In fact. I want to read that story. Anybody have suggestions?

Update: Virgina Hughes has more coverage of the Dias and Ressler paper, which has since been published at Nature Neuroscience.

1 Comment

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

[…] Places is, for the most part, a blog about watery landscapes. Some detours into neurobiology, epigenetics, animal friendships, and children’s literature aside, I usually manage to stay focused on […]