Sandy’s Anniversary and Our Watery Future

October 29 marks the one-year anniversary of “Superstorm” Sandy’s landfall in Brigantine, New Jersey.

Second only to Hurricane Katrina in terms of damages, the storm wrought havoc across the region, devastating coastal communities and leaving millions without power. An interactive map produced last year by the New York Times surveyed the devastation Sandy inflicted across New Jersey and New York. It’s worth revisiting some of last year’s photography to remember just how staggering the impact was.

The Atlantic has a striking set of before/after photo pairs commemorating the anniversary of Sandy’s destruction. There’s also a remarkable story in the New York Times about how the city’s subway system fared during the disaster. It offers some real insight into all the invisible infrastructure—including intangible stuff like human experience—that not only makes the system work in general, but also helped ensure things didn’t go much, much worse. Also worth checking out amidst the flurry of anniversary articles and blog posts (ahem) is Rethink, Rebuild, a special series from the Atlantic Cities blog on Sandy and resilient design.

Rethink, Rebuild focuses on Rebuild By Design, a competition in which ten teams of multidisciplinary experts—including planners, engineers, architects and social scientists—submitted proposals for future development in the region. One of the major concerns of Rebuild By Design is our watery future. Over the next century, climate change and rising sea levels are set to dramatically increase the frequency and intensity of coastal flooding.

A recent piece over at Nature clarifies just how complicated it is to predict the rate, extent, and geographical variability of rising seas. For example, air pressure, winds, and ocean currents have worked together to make sea level rise at 3 to 4 times the global average rate along a stretch of the North Carolina coast. Meanwhile, New York City’s Panel on Climate Change estimates that seas will rise locally between 30-60cm (about 1 to 2 feet) by 2050. That may not sound like much, but combine that base height with another major storm surge and the results would be catastrophic.

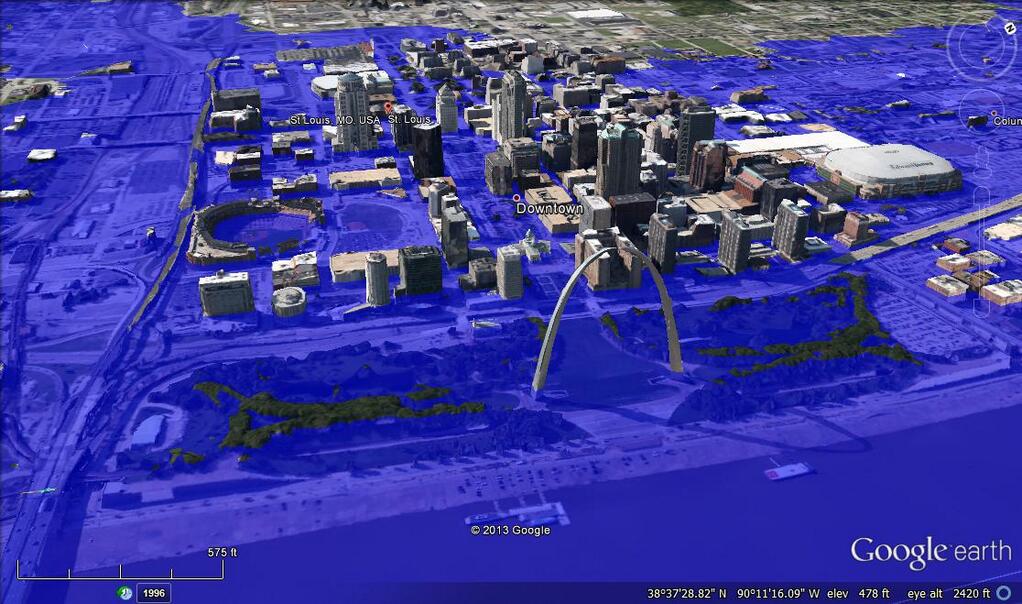

For the really apocalyptically minded, there’s the “What Could Disappear” feature from the New York Times. An interactive slider allows users to flood American cities from Baltimore to Wilmington with between 5 feet (predicted in 100 to 300 years) and 25 feet (waaaaay down the line) of water. Along similarly apocalyptic lines, the #DrownYourTown hashtag on Twitter recently saw marine biologist Andrew David Thaler create on-demand visualizations for drowned cities all over the world.

The unlikely scenarios behind #DrownYourTown aside, it’s still clear that many coastal regions are facing watery futures. But rather than indulge in some Ballardian nightmare, planners, landscape architects, geographers, and many more are trying to imagine a future in which water is partly welcomed into urban landscapes in productive, carefully managed ways. These “soft-infrastructure” approaches to dealing with rising sea levels and powerful storm surges re-imagine human settlements as fundamentally more permeable places.

In the Netherlands, the Room for the River program is working to lower dikes, create spillways for high water, and return drained land to marshes and floodplains. New York City has seen proposals to reconnect people to the waterfront, for marshy green spaces that would buffer floodwaters, and for restored oyster reefs that would absorb waves and provide other ecological services. Oyster-tecture, developed by landscape architect Kate Orff, is, frankly, just a really amazing project for so many reasons. Check out her Ted Talk:

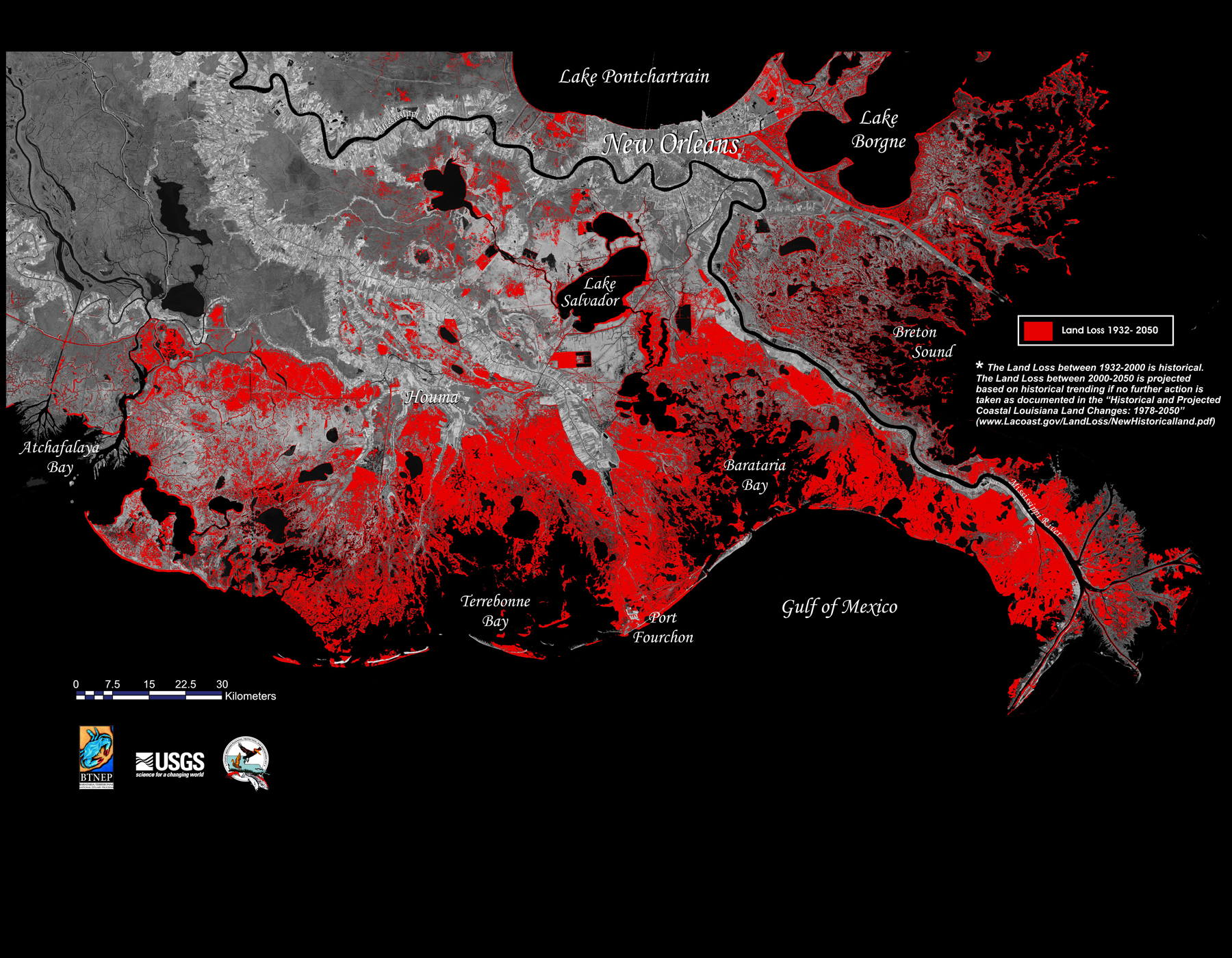

These kinds of ideas are also developing in Louisiana, where sea-level rise is combining with sinking and eroding coastal wetlands to make for a particularly sodden future.

Dutch Dialogues and Gutter to Gulf are two big projects aimed at rethinking the place of water in both New Orleans and the southern Louisiana landscape in general.

Both projects advocate for water as an ecological, economic, and infrastructural amenity, and envision a permeable city in which water gets integrated into, rather than excluded from, urban lives. Proposals include:

- Storing and circulating water in New Orleans

- Reviving and reconnecting waterways

- Restoring wetlands

- Developing urban aquaculture and rice agriculture

- And even Redistributing river sediment across the sinking landscape.

There are, of course, major obstacles to implementing some of these proposals. They require enormous political will and vast redirection of both resources and institutional inertia (see: the Army Corps of Engineers). Moreover, questions of inequality and social justice cannot be ignored when we’re talking about retreating from floodplains or transforming urban spaces into wetlands and aquacultural farms.

But, overall, I like to think these new water imaginaries emerging in New Orleans, New York, the Netherlands, and elsewhere offer a great deal of hope for the future. People have inhabited watery places for thousands of years, but the last few centuries have seen humans increasingly eliminate water from their landscapes through drainage, levees, pumps, buried streams, and so on, often with significant ecological and social costs (Hurricane Katrina being a great example). These new efforts to promote a visible, working presence for water in urbanized environments suggest a turning point in our relationship to wetlands and shorelines. Although it’s taken awful tragedies like Katrina and Sandy to inspire them, these new visions hold the promise of a wet–land ethic for our watery future.

1 Comment

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

[…] in October of this year and the event inspired a ton of fascinating writing. You can check out both my roundup and the superior one over at Urban Omnibus. Two Sandy anniversary stories stood out in particular, […]