Following Up on Animal Daydreams

In early August, I wrote a piece about the surprises of interspecies friendships. That post concluded with some striking images of koalas both seeking out human infrastructure and begging for water in the midst of an unusually intense Australian heat wave in 2009.

Allow me to gauchely quote myself:

It looks as if these wild animals left their eucalyptus forests to search for water in decidedly human landscapes. While we’re constantly observing our non-human neighbors, how often do we stop to think about the ways they’re observing us? How much do these creatures recognize humans and our activities? Did they just know that by following roads or “breaking into” homes, they would find relief? Will we see more wild animals reaching out to humans as climate change makes for increasingly extreme weather around the world?

Serendipitously, both Eric Jaffe at The Atlantic Cities and Carl Zimmer for the New York Times recently reported on new research offering food for thought around just these questions. Titled “Anthropogenic environments exert variable selection on cranial capacity in mammals,” the article appeared just a few weeks ago in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Let’s translate that headline. The study suggests that particularly human places (“anthropogenic environments”) like cities and agricultural landscapes tend to see an increase in brain size (“cranial capacity”) in some mammals.

Author Emilie C. Snell-Rood is an evolutionary biologist working at the University of Minnesota. Using specimens from the university’s Bell Museum collection, she and an undergraduate assistant, Naomi Wick, examined the skulls of between 25 and 50 specimens of 10 different mammals species, including shrews, gophers, mice, squirrels, voles, and bats.

Science writer Carl Zimmer summarizes their conclusions much more nicely than I ever could:

Two important results emerged from their research. In two species — the white-footed mouse and the meadow vole — the brains of animals from cities or suburbs were about 6 percent bigger than the brains of animals collected from farms or other rural areas. Dr. Snell-Rood concludes that when these species moved to cities and towns, their brains became significantly bigger.

Dr. Snell-Rood and Ms. Wick also found that in rural parts of Minnesota, two species of shrews and two species of bats experienced an increase in brain size as well.

Dr. Snell-Rood proposes that the brains of all six species have gotten bigger because humans have radically changed Minnesota. Where there were once pristine forests and prairies, there are now cities and farms. In this disrupted environment, animals better at learning new things were more likely to survive and have offspring.

Snell-Rood and Wick’s findings got me thinking in two ways.

First, it reminded me of several places where wild species unexpectedly thrive in fundamentally human places:

Coral reefs emerge from decommissioned oil rigs (although not without problems).

The Salton Sea, a highly polluted body of water born out of human error, provides a critical resting spot for magnificent flocks of waterfowl and other birds migrating along the Pacific Flyway. Although, again, not without problems.

Hedgerows in the United Kingdom, although thoroughly human creations, are increasingly recognized for their unique ecological value.

A 2007 study found that some European forests actually owed their ecological composition to forgotten peasant traditions of collecting and removing leaf litter from the forest floor. Seemingly wild, these woodlands actually owed their nature to centuries of human intervention.

Finally, there’s always Rocky Mountain Arsenal. Once used for agriculture, its 15,000 acres of prairie and wetland became a chemical weapons manufacturing center during WWII, an agricultural chemical plant at war’s end, and finally a conventional weapons facility during the Cold War. Today, the Arsenal thrives as a wildlife refuge.

And second, Snell-Rood and Wick’s research made me wonder whether the brains of these animals might have the capacity to grow and adapt to all sorts of unusual circumstances wrought by anthropogenic environmental change. Not just in terms of the changes in land-use and land-cover associated with cities, but also the environmental transformations we see emerging thanks to climate change. Maybe those koalas wandering in search of human infrastructure and begging for water really knew what they were doing after all.

And as I shared in that original post, there’s something about such adaptations that are oddly hopeful:

Despite the fact that we’ve done a heck of a job messing with the planet and its inhabitants (both human and not), there’s a strange way in which these images made me feel as if we could all be in this—the Anthropocene—together.

It is, of course, just natural selection doing its thing. There will likely always be at least some organisms out there in the world that have the capacity to adapt to almost whatever we throw at them. Indeed, we have to be careful not to let studies like these or other examples of human/non-human coexistence turn us into environmental Pollyannas.

After all, while the biological changes found by Snell-Rood and Wick suggest certain species might be adapting just fine to urban life, we don’t actually know if there’s a cost to such adaptation.

Still more important is the fact that even if we accept such adaptations as unequivocal goods, not all organisms can adapt in these ways. This kind of coexistence only offers hope for some creatures.

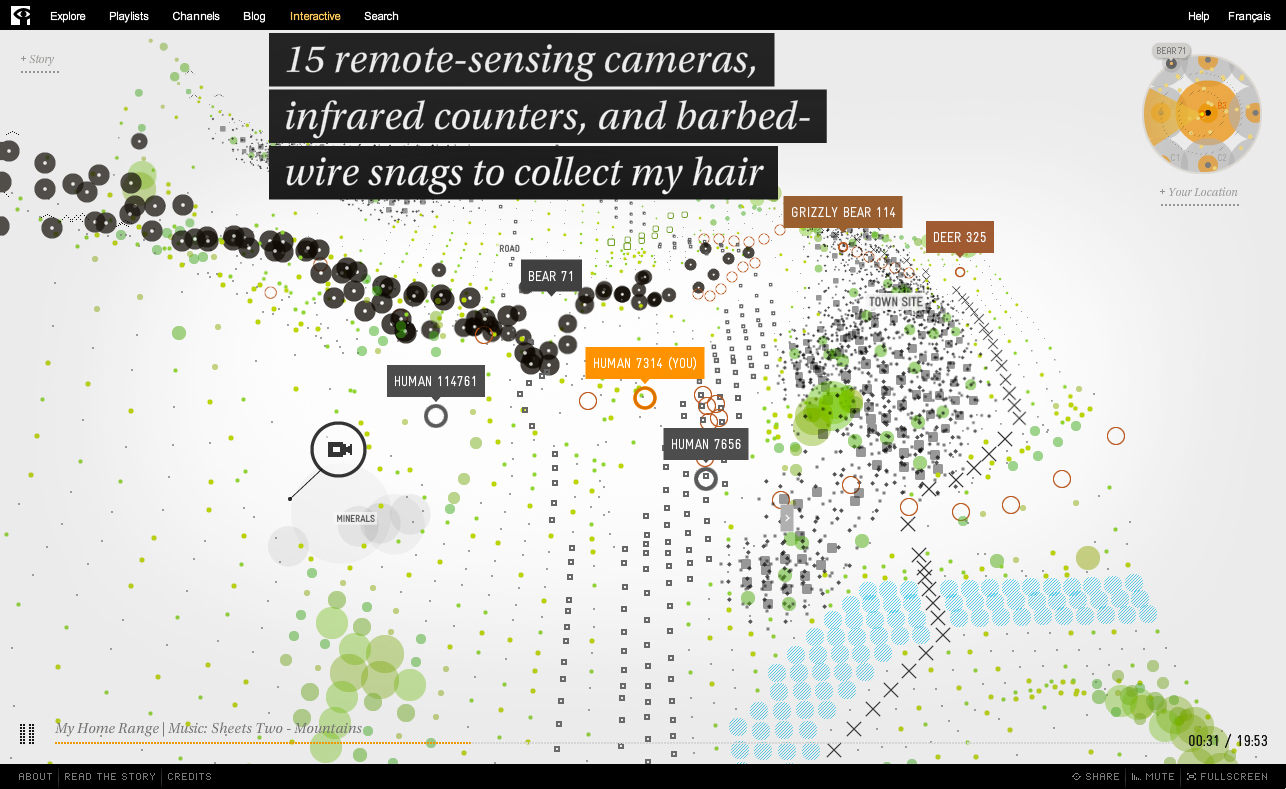

Large predators, for example, are notoriously maladapted to human alterations of the environment that, when compared with urban development, are profoundly subtle. NFB Interactive’s remarkable interactive documentary Bear 71 narrates a poignant case (seriously, set aside 20 minutes and experience it).

And so, despite the hopes evoked by the adaptations Snell-Rood and Wick describe, we humans still present fundamental challenges to survival for those animals sensitive to anthropogenic environmental change.

Wolves and bears are never going to do well in human landscapes.

Nor would we want them to.

Yet, despite those caveats, I’m going to cling to at least some optimism. The story told by Snell-Rood and Wick’s research is one in which there’s room for some wildness in human places and for humanness around some wild creatures. It reminds us that not everything humans do is fundamentally incompatible with non-human nature. And it perhaps even suggests ways we might be more mindful about accommodating wildness even in our most human environments.

As far as I’m concerned, that’s actually a pretty wonderful vision. It suggests many possibilities of coexistence, some of which might help us find a more intentional way of living with the non-human world instead of (futilely) trying to remove ourselves from it.