The Physical Environment 3: Building on Its Own High Ground

This is the third in a series of three introductory posts I’m dedicating to the physical environment of deltaic landscapes. The first post looked at land-building and the timing of delta formation across the globe. The second discussed the quirks of topography in river deltas. Today, I’ll conclude the series by revealing what happens when, as is the case on a deltaic plain, a river occupies the landscape’s high ground.

Holding the high ground?

The Mississippi River’s deltaic plain begins near Baton Rouge, Louisiana. From here down to the Gulf of Mexico, the region’s high ground is always found closest to the river in the form of its natural levees. That the river is constantly surrounded by, and indeed building upon, its own high ground has some pretty remarkable consequences. As the Mississippi lays down new land, it also lengthens. And as it lengthens, the slope of the river flattens, its waters slow, and sediment starts accumulating in the riverbed. Over time, the river ends up being quite a bit higher in elevation than the surrounding territory, natural levees aside.

Since water always takes the path of least resistance, the only things keeping the river in its channel under these conditions are its natural levees. Given a large enough flood, the river could easily overcome its banks to find a much steeper, much more direct path to lower ground. This kind of event—called an “avulsion”—takes place in deltas with some frequency, both at large and small scales.

Small scale: meander cutoffs, meander scars, and oxbow lakes

At smaller scales, avulsions work to cut through meanders (creating a “cutoff”) and form new river channels alongside older ones to produce distinctive patterns of meander scars and oxbow lakes.

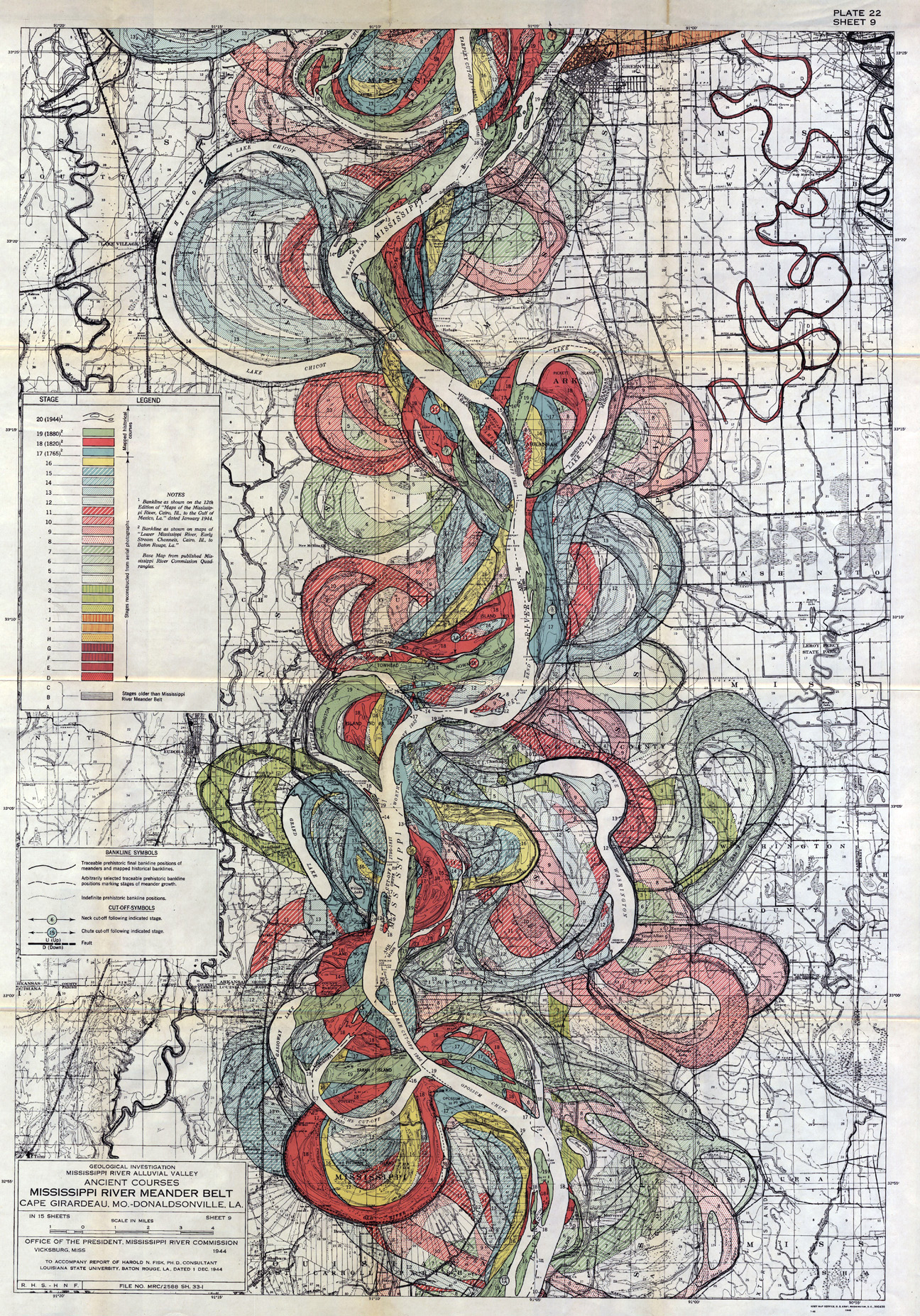

In 1944, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers consultant named Harold Fisk used a spectacular aesthetic sensibility to map these patterns as produced by the lower Mississippi over the last 10,000 years. You can download high-quality PDFs of Fisk’s maps from the Army Corps of Engineers here.

Large scale: “delta switching”

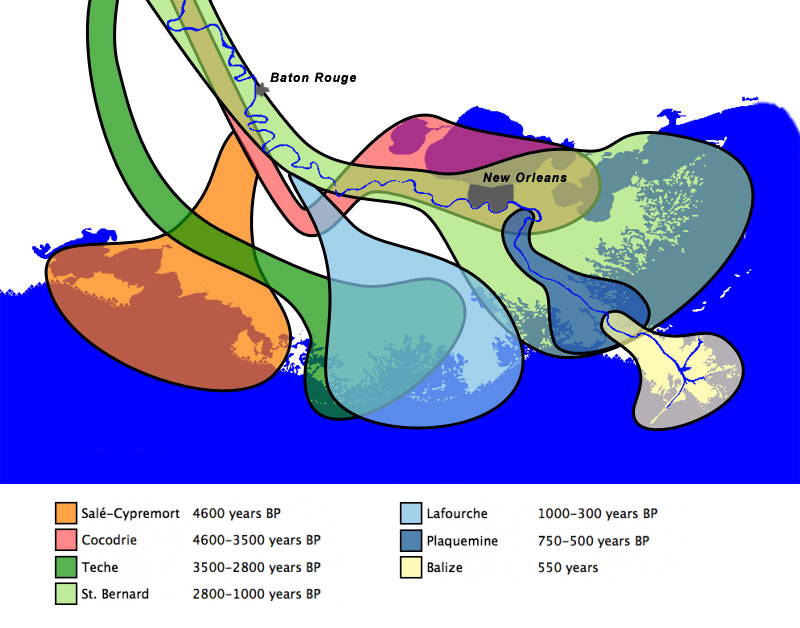

Meanwhile, large-scale avulsions in the Mississippi River have resulted in much more dramatic landscape transformations. In these events, the river spills over to build an entirely new lobe of land out into the Gulf of Mexico. Also called “delta switching,” this process has occurred about seven times over the last 7000-8000 years.

In fact, we’re overdue for another. If it weren’t for a serious piece of infrastructure called Old River Control near Simmesport, La, the Mississippi would likely be flowing down to the Gulf through the mouth of Atchafalaya River, over 100 miles west of the current Balize (or “bird’s foot”) delta of the river. Given that the Mississippi River is one of the world’s busiest commercial waterways, imagine the havoc that would cause not only the city of New Orleans, but also the entire United States.[1. John McPhee told this story with unparalleled skill in a 1987 issue of The New Yorker. You can also read it in his collection, The Control of Nature.]

References

Fisk, Harold. Geological Investigation of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River. Vicksburg, MS: US Army Corps of Engineers, Mississippi River Commission, 1944.

Gupta, Avijit (ed.). Large Rivers: Geomorphology and Management. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2008.

McPhee, John. The Control of Nature. NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1989.

Roberts, Harry. “Delta Switching: Early Responses to the Atchafalaya River Diversion.” Journal of Coastal Research 14, 3 (1998): 882-899.

3 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

[…] few posts ago, I wrote about what happens when a river in high water jumps its banks to find a new channel or even form an entirely new delta. But often a flooding river overcomes its […]

[…] is that? As I’ve discussed previously on this blog (see here, here, and here), coastal Louisiana is a very young, very flat, very muddy landscape. It got built out into the […]

[…] profoundly felt as part of daily life. As I’ve recounted elsewhere on this blog (here and here), southern Louisiana was built up entirely from about 8,000 years of sediments deposited by the […]